Column by Sophie Friot

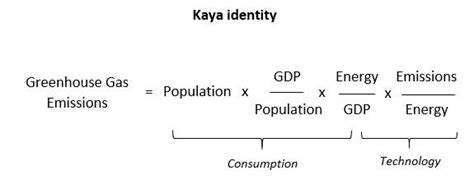

Literature and studies on energy and ecological transitions regularly address Kaya’s identity, analyzing the human impact on the climate and understanding the link between changes in gross domestic product and carbon evolution.

It would be too simple to correlate gross domestic product (GDP) increase with carbon growth, suggesting that the solution to rising greenhouse gases would simply be « de-growth ».

This equation is a “tool” used in many research projects to better identify the levers to move towards an economically sustainable and less carbon-intensive world.

It is used by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) and the International Energy Agency, among others, to analyze changes in CO2 emissions from fossil fuels.

This concept refers to the Japanese economist Yoichi KAYA, who specializes in energy and the environment, and wrote in 1993 his book : “Environment, Energy, and Economy: Strategies for Sustainability”.

More than 30 years ago, it demonstrated that the increase in energy consumption associated with economic development can vary by population level, energy sources, and regions (Western versus developing countries).

It is defined as follows:

The energy intensity component of gross domestic product is the amount of energy required to achieve a result or a production. In Western countries, the energy intensity of the economy has followed a downward trend since the beginning of the industrial era. The sharp decline was caused after the two oil shocks by the development of nuclear energy and renewable energies. Notably, the decrease in energy consumption being smaller than the temporary drop in gross domestic product resulted in the anomaly of the 2020 health crisis period when energy intensity rebounded upwards.

Another component of the equation, closely related to the previous one, is the carbon intensity, as the share of CO2 in total energy consumption.

Carbon intensity has followed the same trend since the early 20th century with the increasing weight of oil and gas in the mix, which emit less CO2 than coal ; the movement has accelerated since the 1980s with the rise of nuclear and renewables, such as wind or photovoltaics.

Following the effects of the 2 oil shocks of the 1970s, developments in gross domestic product and energy consumption needed to be separated. In this case, we are talking about:

– Partial decoupling when emissions grow less rapidly than gross domestic product

– Absolute decoupling is when emissions decrease while gross domestic product increases, which means green growth.

With Trump making shale oil and gas a priority and China still relying on coal for the majority of its energy production, there is still scope to achieve full and global decoupling to meet Net Zero Emissions targets by 2050.

In conclusion, let us remain optimistic because, without total decoupling, partial decoupling is possible by levers such as:

– Improvement of technologies in construction

– Energy renovation of buildings

– Electrification of transport

– Progress towards a less carbon-intensive energy mix: development of renewable energies and reduction in the use of coal in fossil fuels.

In Germany, the closure of the remaining nuclear power plants has not curbed the decline of fossil fuels, such as lignite, in the face of the development of renewable energies.