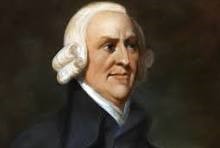

Adam Smith (1723-1790) was, like Turgot, destined for an ecclesiastical career after brilliant studies, the first in Glasgow then in Oxford, and the second at the Sorbonne. They both showed more aptitude for the “applied philosophy” of the then nascent economics, than for theology. While Turgot was inspired by the Physiocrats represented by Quesnay and Gournay, Adam Smith was mainly influenced by the philosophers Hume, Locke, and Hobbes. When Turgot was administering a French province, Smith was teaching economics in Glasgow and Edinburgh, before becoming a customs commissioner like his father. The two men met in 1770 and, according to Condorcet, exchanged letters (now lost) mainly on the theme of the creation of economic value.

The Theory of Moral Sentiments

Smith became known with the publication in 1759 of the Theory of Moral Sentiments, inspired by Hume’s book published in 1738, A Treatise of Human Nature. Smith defends the principle of utility – “man acts to please himself and to avoid pain” – as well as the principle that the human brain works by “associations of ideas”. Unlike Hume, Smith argues that man is guided by his personal interest, but also by the judgment of others and by the “sympathy” he feels for his fellow men. Smith opposes the purely mechanistic conception of a society based on commercial exchanges. He maintains, however, that the social order is “by nature” unequal, and that access to wealth requires the exercise of virtue. According to him, moral satisfactions are more important than material benefits. As a true Stoic, he regrets that wealth is preferred to wisdom, and observes that “we have a disposition to sympathize with the passions of the rich and the great”. Smith is aware of the opposition between social justice and economic order, unlike the physiocrats who claim that justice depends only on economic and social progress. He believes that freedom is the condition of progress, but that it generates “acceptable social inequalities”.

The First Economic Reflections

In 1763, Smith taught the theory that “opulence is born from the division of labor” in Glasgow. In order to “show the usefulness of the use of machines”, he presents the famous example of the manufacture of pins, summarized by the formula “If a man had to make a pin entirely alone, by going himself to look for the raw material in the ground, it would take him a year to make a single pin”. He opposed the physiocrats who considered industrial activities to be “sterile”, but Turgot was always reserved about this anti-industrial bias. Smith also recognizes that farms and industrial factories require capital to increase labor productivity. He believes that trade is the best way to enrich merchants and allow them to create factories. Following Petty and Locke, he laid down the principle that “the natural price of commodities and objects is measured by the labor intended to produce them”.

The Wealth of Nations

In 1776, the same year that Turgot left his ministry, Smith published his major work, An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations. He makes a fundamental distinction between use value and exchange value. “Things that have great value in use often have little or no value in exchange”. These two notions of value are, according to him, “social facts”. The exchange value of an object is based in principle on the amount of work required for its production, but it is also determined by the profit – or income – of the capital used to manufacture it. His book capital lays the foundations of a new theory of income. He concluded that national wealth increases with the demand for labor but also with the increase in capital. The allocation of capital is a function of the risk that accompanies the type of business in which it is used. The interest rate of borrowed capital must be lower than the rate of profit of the capitalist, to cover his risk. Smith applies the same reasoning to land rents, although less risky than industrial profits. The accumulation of capital depends mainly on the savings of manufacturers and merchants, because “what is saved annually by workers is also regularly consumed and it is almost at the same time.” He thus foreshadows the law of natural markets of Jean-Baptiste Say, which was highly disputed.

Smith is also interested in the wages of “unproductive workers” (civil servants, professionals, domestic workers, etc.), whose incomes depend on the wages of “productive workers” and the income of “capitalists”. Smith’s “plan of nature” is simple: capital finances agriculture, then industry and trade, especially foreign trade (the East India companies). Like Turgot, he attributes a limited role to the State and Justice, only responsible for limiting certain inequalities and developing competition between productive workers and entrepreneurs. Smith thus built a “transfer system” or an “economic table” more relevant than those of Quesnay and Boisguillebert.

Smith also opposed the mercantilist system, considering that it artificially diverted capital intended for domestic production. Like Hume, he was in favor of importing products that cost less than domestic products. He also supports exports when they help support the domestic industry: “the effect of the colonies’ trade is to open a vast, albeit distant, market for those parts of the English industry’s product that may exceed the demand of more distant markets… “. But he considers, on the whole, that the external outlets are only a “temporary adjuvant” in the process “which can only delay the inevitable moment when we will reach the stationary state in which society has reached the full measure of the wealth of which it is susceptible”. Like Turgot, he believes that the slavery in force in the colonies for economic reasons is destined to disappear.

The legacy of Adam Smith

The posterity of Adam Smith is immense. He is still considered the founder of economic liberalism and is still often quoted, although his thoughts have raised much criticism during his lifetime and during the nineteenth century. He was accused of opposing the interests of manufacturers and traders to the general interest, on the one hand, and the interests of workers to those of the capitalists, on the other hand. His reasoning was disputed because it would lead to a stagnation of the value of agricultural products and a devaluation of industrial products (under the effect of progress), and to a drop in rents and profits, which was not observed during the 1st industrial revolution and was unevenly observed during the 2nd industrial revolution.

J-J. PLUCHART