When one rereads the economic history of France, it seems that in every era, a voice has reminded us of the same simple truths: one must not spend what one does not have, one must not play with money, and one cannot build prosperity on promises or wagers.

Turgot, Jacques Rueff, and Jean-Marc Daniel embodied this fidelity to reality.

Each, in his own century, defended the idea that balancing public finances is not a constraint but a condition of freedom. Their legacy has endured through time, tracing a red thread from the eighteenth century to the present day.

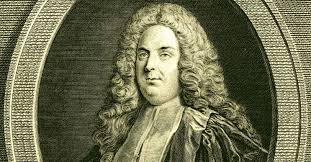

Turgot: Rigor as a Starting Point

When Turgot was appointed Controller-General of Finances, he found a state in fiscal disorder. He rejected privileges and denounced waste.

His guiding principle can be found in his Reflections on the Formation and Distribution of Wealth (1766), where he wrote: “We do not create wealth by distributing what we do not have.”

This sentence, often quoted, expresses more a philosophy than an economic theory: rigor is not an accounting obsession, it is a moral requirement.

For him, a deficit is an injustice passed on to future generations.

In a France bogged down by rents and privileges, he defended the freedom to work, the free circulation of grain, and the abolition of forced labor.

Jacques Rueff: The Guardian of Monetary Truth

A century and a half later, Jacques Rueff took up the torch.

He too lived in a world of illusions — those of a misinterpreted Keynesianism and of deficit financing through monetary creation.

Alongside General de Gaulle, he helped lead the 1958 fiscal recovery of the French economy.

For him, public debt was not just a number but a political fault.

In The Social Order, he wrote: “No order can be built by defying the natural laws of the economy.”

Budgetary balance, in his eyes, was an instrument of sovereignty: every deficit, every indulgence, led to dependency.

He saw money as a moral instrument before being a financial one.

In The Relentless Problem of Balance of Payments, he extended Turgot’s spirit: without fiscal discipline, there can be no lasting freedom.

Rueff rejected fatalism. In Unemployment and Money, he demonstrated that unemployment results from accumulated rigidities.

He advocated greater labor-market flexibility and the defense of free competition.

Jean-Marc Daniel: Growth Through Freedom and Responsibility

Jean-Marc Daniel stands in this same lineage. A liberal economist, he rebukes Keynesian complacency.

His work belongs to a globalized, open economy where the temptation of protectionism and public spending remains strong.

His intellectual mission: to remind us that sustainable growth rests on four essential pillars — work, saving, freedom (competition), and education.

For him, rigor goes hand in hand with pedagogy.

The State cannot produce wealth; it can only guarantee the conditions for it: security, justice, education, and monetary stability.

Economics, in his eyes, is not a machine — it is a moral order founded on the truth of prices established by free competition and the reward of effort.

In this sense, Daniel is a continuator of Turgot and Rueff: he denounces public budgetary excesses and insists that prosperity cannot be decreed — it must be learned.

Philippe Aghion: Creative Continuity

Philippe Aghion extends this heritage into another dimension — that of innovation.

Where Turgot saw rigor as the condition of freedom, and Rueff viewed sound money as the keystone of prosperity, Aghion introduces the discipline of creativity.

Inspired by Schumpeter, he formalized creative destruction: progress does not come from a spendthrift state but from a stable framework in which firms are free to innovate, fail, and begin again.

Like his predecessors, Aghion does not oppose innovation and rigor — he connects them.

Without strong institutions, quality education, and incentives for effort and investment, there can be no lasting progress.

In this sense, he continues the spirit of Turgot and Rueff: freeing human energy while maintaining the discipline of rules.

He also joins Daniel in emphasizing the importance of knowledge and education.

Conclusion

From Turgot to Rueff, from Daniel to Aghion, four voices, four centuries, one lesson: discipline — whether fiscal, monetary, or intellectual — is not optional; it is a political necessity.

Economic disorder always prepares social disorder and, ultimately, leads to servitude, while rigor opens the path to freedom.

Turgot’s thought has endured because it is rooted in reality and rejects illusions.

Its legacy endures because success does not lie in mortgaging the future but in giving it every chance to exist free of servitude.

To reread Turgot, Rueff, Daniel, and Aghion is not to yield to nostalgia; it is to rediscover, beneath today’s debates, the keys to lasting prosperity.

Benoit Frayer November 2025

References

Anne-Robert Jacques Turgot, Reflections on the Formation and Distribution of Wealth (1766).

Jacques Rueff, The Social Order (1945); The Relentless Problem of Balance of Payments (1965); Unemployment and Money (1931).

Jean-Marc Daniel, Capitalism and Its Enemies (2016); The Collusive State (2014); A Living History of Economic Thought (2018).

Philippe Aghion, The Power of Creative Destruction (with Céline Antonin and Simon Bunel, 2020); Endogenous Growth Theory (with Peter Howitt, 2008).

Joseph Schumpeter, Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy (1942) — theoretical foundation of “creative destruction,” later extended by Aghion.

Benoit Frayer November 2025