On September 12, Fitch downgraded France’s sovereign debt from AA- (high quality) to A+ (upper average quality).

In its analysis, the agency uses GDP as a central indicator to assess the sustainability of public finances, in particular through the debt/GDP ratio.

Fitch points out that French public debt is expected to rise from 113.2% of GDP in 2024 to 121% in 2027, with no clear prospect of stabilization.

Fitch considers it unlikely that France will bring its public deficit below 3% of GDP by 2029, while the government was aiming for this objective to comply with European rules. The deficit is expected to be 5.4% of GDP in 2025, and should remain above 5% in 2026 and 2027. In this context, the agency believes that France has less room for maneuver in the face of possible economic shocks.

According to the latest INSEE estimates, the country’s GDP will grow by 0.8% in 2025 instead of the 0.6% initially forecast, due to better dynamics in agriculture, tourism, the real estate market, and aeronautics. This increase, although positive, is far from expected to offset the weight of the debt.

In its latest economic bulletin published on September 25, the ECB presents an overview of the macroeconomic projections of inflation and GDP in the Eurozone, in order to justify its monetary policy. Inflation is expected to be 2.1% in 2025, 1.7% in 2026, and 1.9% in 2027. Growth, meanwhile, is expected to be 1.2% in 2025, 1% in 2026, and 1.3% in 2027. In its statement, “the Governing Council considers it essential to strengthen, without delay, the eurozone and its economy in the current geopolitical environment. Fiscal and structural policies should improve the productivity, competitiveness and resilience of the economy… It is up to governments to prioritize structural reforms and strategic investments that promote growth while ensuring the sustainability of public finances.”

The roadmap is therefore clear: GDP must be supported

However, is the calculation of GDP still relevant and up-to-date to measure the wealth created by a country? Should its formula evolve as suggested by some economists and politicians? And especially in terms of climate change?

GDP is already 80 years old

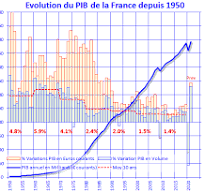

It was at the Bretton Woods conference in 1944 that GDP was adopted as a standard indicator to measure the economic activity of countries, in particular to facilitate international comparisons and post-war reconstruction. It will thus be gradually adopted by the whole world and international organizations, such as the UN, the IMF or the World Bank. In France, it was applied from 1949.

Over the years, GDP gradually replaced GNP (Gross National Product) as the main indicator, because it measures production in a territory, regardless of the nationality of the economic actors.

In the 70s and 80s, GDP began to include previously neglected sectors such as services. Indeed, developed countries are moving from an industrial economy to a service economy, which changes the structure of GDP

The limits of GDP

In 2009, the Stiglitz-Sen-Fitoussi report or the “Report on the measurement of economic performance and social progress” was commissioned by Nicolas Sarkozy. Questioning the limits of the calculation of the indicator, this report proposes to supplement the GDP with indicators of well-being, sustainability and inequalities.

Indeed, the report points out that GDP:

– ignores well-being: it does not measure happiness, health, education, or the quality of the environment;

– neglects inequalities: an increase in GDP can hide an increase in income gaps. It ignores sustainability: It does not take into account the degradation of natural capital (resources, climate);

– does not value unpaid work, such as volunteering or domestic work.

Recently, the ECB also warned its member states that climate change could cut European GDP by 5% by 2030.

In France, INSEE proposed in 2024 a complementary indicator to GDP, the “adjusted net domestic product” (Pina): this indicator makes it possible to take climate change into account by netting the creation of value from the effects of future damage and decarbonization costs.

Although developments are being studied and considered, GDP is still the reference for a large number of institutions as a management tool; but other dimensions of analysis will have to be added in order to have a more global vision in a context of global warming.

Sophie Friot

Member of the Turgot Club